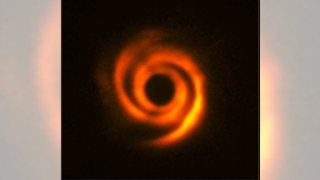

Star system with galaxy-like 'arms' may be holding a secret planet

A distant star system has Milky Way-like spiral arms orbiting it. New research suggests a giant planet may be to blame.

Our Milky Way galaxy is a collection of stars famously arranged in a series of spiral arms wrapped around a black hole center. But galaxies aren't the only spiral structures in the universe; individual stars can have swirling, spiral arms as well. And new research is helping to unravel how — and why — they form.

A new study published July 6 in the journal Nature Astronomy describes how a giant planet might be generating spiral arms in the dusty disk encircling its star. "Our study puts forward a solid piece of evidence that these spiral arms are caused by giant planets," lead study author Kevin Wagner, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, said in a statement.

The exoplanet, called MWC 758c, lies in a very young star system about 500 million light-years from Earth. Its parent star still sits in the center of a protoplanetary disk — an amalgamation of dust and rocky objects that have not yet condensed into planets, moons and asteroids.

MWC 758c is a gas giant with about twice the mass of Jupiter. The researchers think this giant planet's gravitational heft allowed it to sculpt the protoplanetary disk in which it sits by stretching the surrounding gas into long arms as the planet orbited its host star. Jupiter may have once played a similar role in shaping our solar system, the team added.

This particular protoplanetary disk was discovered in 2013, but scientists hadn't been able to confirm that MWC 758c existed until now. It turns out, the gas giant was difficult to see because it is extremely red. Longer, redder wavelengths of light are notoriously difficult to pick up with ground-based telescopes. But the team used the Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer in Arizona, one of the most red-sensitive telescopes ever built.

MWC 758c's redness might help to explain why gas giants haven't yet been spotted orbiting other spiral protoplanetary disks. The researchers hope to confirm their observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) next year.

"Depending on the results that come from the JWST observations, we can begin to apply this newfound knowledge to other stellar systems, and that will allow us to make predictions about where other hidden planets might be lurking," Wagner said.

Live Science newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest science news by signing up for our Essentials newsletter.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.

Most Popular

By Tom Metcalfe

By Keith Cooper

By Sascha Pare